While Java 9 has reached its end-of-life earlier this week, the Java Platform Module System (JPMS, JSR 376) is here to stay. This means also specifications such as the Java Persistence API or Bean Validation will eventually have to be adjusted to support and take advantage of the module system.

This blog post is the first of a series on exploring JPMS modularity patterns for specification APIs. In this part we’re going to look into how implementations of a specification API can be bootstrapped in a portable way and how such implementations can access the private state of modules of the user of the API. As discussed a while ago, the latter is a common requirement; for instance JPA providers must do so for reading and writing entity state.

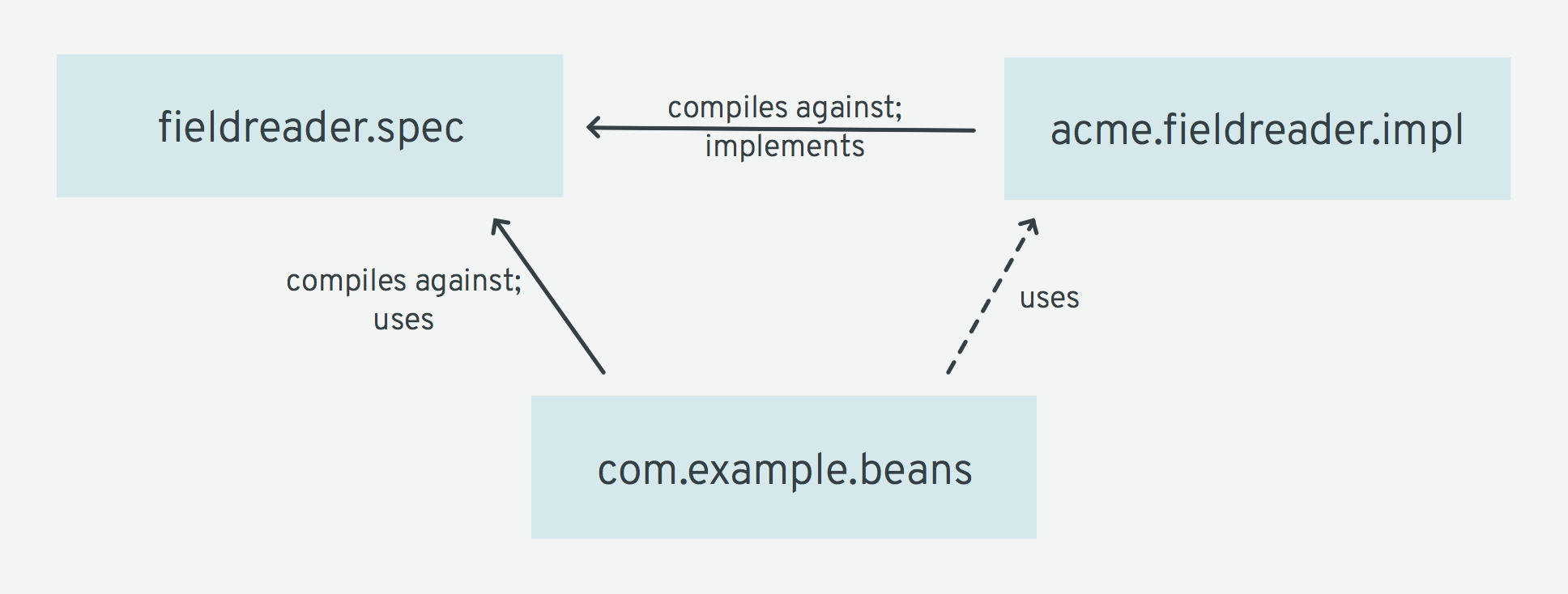

As an example, let’s consider three JPMS modules:

-

fieldreader.spec: a made-up "specification" which defines a contract for accessing private fields of user classes

-

acme.fieldreader.impl: ACME Corp.'s implementation of the field reader spec

-

com.example.beans: a module with a user class and some application code that uses the field reader spec API to access the private state of that user class

The following picture shows the relationships between the modules:

Both the ACME spec implementation and the user module depend on the spec API module at compile and run time.

But the com.example.beans module shouldn’t depend on any specifics of the ACME implementation of the spec,

i.e. at compile time it will only depend on the API module, whereas the ACME implementation module is a run time only dependency.

With this structure in mind, let’s explore how the API, the implementation and the code using the API could be designed.

The Specification API

The field reader spec defines a single interface, FieldValueReader:

/**

* Retrieves the value of the specified (private) field from the given object.

*/

public interface FieldValueReader {

public Object getFieldValue(Object o, String fieldName);

}Passing an object and a field name, the API should return the value of the given field. Obviously, that’s not an overly useful spec to have, but it serves well as an example here, as its implementation leads to some interesting challenges, similar to the ones one would encounter with a real spec such as JPA.

We also need a way to allow code in other modules to bootstrap an implementation of the field reader spec.

Similar to existing specifications (think of JPA’s Persistence or Bean Validation’s Validation classes), this can be realized using a static method on an API entry point class:

public class FieldReaderApi {

public static FieldValueReader getFieldValueReader() {

// ...

}

}Besides any exception and enum types, this entry point class usually will be the only class in the API module which isn’t an interface and provides actual method implementations.

Bootstrapping API Implementations

The implementation of the entry point class can be based on the service loader mechanism. An official part of the Java platform since release 6, the service loader gained much more prominence when the JPMS was introduced.

In JPMS, services are a first-level construct and the means of binding API contracts in one module to implementation(s) located in other modules. To make use of this mechanism, a service contract is needed which serves as integration point between API module and implementation module(s):

/**

* Contract between the field reader API bootstrap mechanism and spec implementations.

*/

public interface FieldReaderProvider {

FieldValueReader provideFieldValueReader();

}In the API’s module descriptor we declare the usage of this service and also export the two API packages:

module fieldreader.spec {

// public API

exports fieldreader.spec;

exports fieldreader.spec.bootstrap;

// using the FieldReaderProvider service

uses fieldreader.spec.bootstrap.FieldReaderProvider;

}Now the getFieldValueReader() method of FieldReaderApi can be implemented with a few lines of code:

public class FieldReaderApi {

public static FieldValueReader getFieldValueReader() {

ServiceLoader<FieldReaderProvider> loader = ServiceLoader.load( FieldReaderProvider.class );

return loader.findFirst()

.orElseThrow( () -> new IllegalStateException(

"No provider of " + FieldReaderProvider.class.getName() + " available" )

)

.provideFieldValueReader();

}

}Providing a spec implementation

It’s now time to take a look at the ACME implementation of the spec.

We first need to create an implementation of the FieldReaderProvider contract

(which will return ACME’s FieldValueReader implementation):

public class AcmeFieldReaderProvider implements FieldReaderProvider {

@Override

public FieldValueReader provideFieldValueReader() {

// ...

}

}We then need to register that service implementation in the module descriptor using the provides directive:

module acme.fieldreader.impl {

requires fieldreader.spec;

provides fieldreader.spec.bootstrap.FieldReaderProvider

with acme.fieldreader.impl.AcmeFieldReaderProvider;

}We also need the requires instruction for declaring the dependence to the API module,

since this module implements the specification interfaces.

With that, the code in FieldReaderApi will be able to bootstrap the implementation.

Towards a FieldValueReader implementation

So far things look pretty much the same as in pre-JPMS times. After all, utilizing the service loader for bootstrapping API implementations in a portable way is an established pattern, used by a wide range of Java specifications. Only the registration of provided and used services in module descriptors is a new facet when using the JPMS.

Things are getting more interesting when it comes to the ACME implementation of the FieldValueReader contract.

One of the goals of JPMS is encapsulation, i.e. non-exported packages and their contents are by default not accessible for code in other modules.

This means that, unlike in the past, the ACME module cannot simply use reflection to obtain a java.lang.reflect.Field instance, call setAccessible(true) on it

and use Field#get() to obtain the field’s value from a given instance.

Instead, for this to work, a package with types to obtain field values from has to be opened towards the ACME implementation module.

Only if that’s the case, we can use reflection or, better yet, the new VarHandle API to get values from private fields in the user module.

There are multiple ways for opening up a package, which each provide a different level of granularity.

The simplest is to make the com.example.beans module a completely open module. This means that code in any other module can apply deep reflection to any type of the com.example.beans module. Needless to say that this isn’t very desirable in terms of encapsulation.

We get some more control by just opening up a single package:

module com.example.beans {

requires fieldreader.spec;

opens com.example.beans;

}This allows any other module to apply deep reflection to the types of the com.example.beans package,

but not to other packages of that module.

That’s already better, but it’d be even more preferable to specifically control and limit which other modules are allowed to do so.

This can be achieved by qualifying the opens directive:

opens com.example.beans to acme.fieldreader.impl;Now we could go and create an implementation of the FieldValueReader interface in the ACME module.

But, thinking about it, we are now in conflict with the original design we set up above:

the user module shouldn’t rely on any specific implementation of the field reader spec, but that’s exactly the case now.

By using the acme.fieldreader.impl module name in our module descriptor, portability to other implementations of the field reader spec is diminished.

Instead of opening up our package towards a specific implementation, it’d be preferable to open it up towards the API module itself:

opens com.example.beans to fieldreader.spec;That’s ideal from a user’s perspective, but the question is, how could this be implemented? After all, the code performing the private field access will be located in the implementation module and not the spec module itself.

Propagating Opened Packages

At this point it comes in handy that it is possible for a module to which a package has been opened to also open this package to other modules.

This means that if the com.example.beans package is opened towards the fieldreader.spec module,

this spec module can also open the package to implementation modules.

To do so, let’s change the FieldReaderProvider interface a little bit:

public interface FieldReaderProvider {

FieldValueReader provideFieldValueReader(PackageOpener opener);

public interface PackageOpener {

void openPackageIfNeeded(Module targetModule, String targetPackage, Module specImplModule);

}

}provideFieldValueReader() has a PackageOpener parameter now.

This object will later on be used in the implementation of FieldValueReader#getFieldValue() to request that given packages from the user’s module should be opened towards the implementation module.

But first let’s take a look at the changes required to the FieldReaderApi class:

public class FieldReaderApi {

private static final PackageOpener PACKAGE_OPENER = new PackageOpenerImpl();

public static FieldValueReader getFieldValueReader() {

ServiceLoader<FieldReaderProvider> loader = ServiceLoader.load( FieldReaderProvider.class );

return loader.findFirst()

.orElseThrow( () -> new IllegalStateException(

"No provider of " + FieldReaderProvider.class.getName() + " available" ) )

.provideFieldValueReader( PACKAGE_OPENER );

}

private static class PackageOpenerImpl implements FieldReaderProvider.PackageOpener {

@Override

public void openPackageIfNeeded(Module targetModule, String targetPackage,

Module specImplModule) {

if ( !targetModule.isOpen( targetPackage, specImplModule ) ) {

targetModule.addOpens( targetPackage, specImplModule );

}

}

}

}The getFieldValueReader() method is pretty much the same as before, it still uses the service loader to find FieldReaderProvider implementations.

What’s different is that it passes an implementation of PackageOpener now.

This class simply opens the given package of the user’s module towards the given spec implementation module, if that’s not the case yet (i.e. if the user’s module is an open module or already opens the given package to the implementation module, nothing needs to be done).

Implementing the FieldValueReader Interface

With these changes in place, it’s finally time to take a look at the FieldReaderProvider and FieldValueReader implementations in the ACME module.

The former is trivial, it just instantiates the field reader, passing along the given opener object:

public class AcmeFieldReaderProvider implements FieldReaderProvider {

@Override

public FieldValueReader provideFieldValueReader(PackageOpener opener) {

return new FieldValueReaderImpl( opener );

}

}The FieldValueReader implementation is a bit more complex:

public class FieldValueReaderImpl implements FieldValueReader {

private final ClassValue<Lookup> lookups;

public FieldValueReaderImpl(PackageOpener packageOpener) {

this.lookups = new ClassValue<Lookup>() {

@Override

protected Lookup computeValue(Class<?> type) {

if ( !getClass().getModule().canRead( type.getModule() ) ) {

getClass().getModule().addReads( type.getModule() );

}

packageOpener.openPackageIfNeeded(

type.getModule(),

type.getPackageName(),

FieldValueReaderImpl.class.getModule()

);

try {

return MethodHandles.privateLookupIn( type, MethodHandles.lookup() );

}

catch (IllegalAccessException e) {

throw new RuntimeException( e );

}

}

};

}

@Override

public Object getFieldValue(Object o, String fieldName) {

try {

VarHandle varHandle = lookups.get( o.getClass() )

.unreflectVarHandle( o.getClass().getDeclaredField( fieldName ) );

return varHandle.get( o );

}

catch (Exception e) {

throw new RuntimeException( e );

}

}

}In getFieldValue(), a VarHandle is used to obtain the value from the specified field of the given instance.

Put simply, var handles (and their siblings, method handles) can be used as an alternative to the classic reflection API for accessing Java fields and methods in a dynamic way.

Var handles are obtained from the MethodHandles.Lookup class. For our purposes it’s important that the lookup has "private access" to the type of the given object. Quoting the docs, "we say that a lookup has private access if its lookup modes include the possibility of accessing private members".

To get a lookup with private access, MethodHandles#privateLookupIn() can be used.

For this to succeed, this call must be made from within a module towards the package of the given type has been opened

(or the type’s own module).

As the call is made from the ACME implementation module,

the PackageOpener passed by the spec module is used to establish this opens relationship, if needed.

This in turn requires that the module to which the package should be opened reads the module declaring the package.

Naturally, the ACME implementation module cannot declare a requires directive towards the user module in its module descriptor.

This is why the reads relationship is established dynamically by calling Module#addReads() before requesting to open the package.

FieldValueReaderImpl takes advantage of the very useful ClassValue class,

which serves as a lazily populated cache for the lookup objects for each type to obtain field values from.

If no Lookup is stored yet for a given type, the computeValue() method is invoked to retrieve such lookup.

All subsequent calls to getFieldValue() for the same type will re-use the lookup instance cached in the ClassValue instance.

Of course a more sophisticated implementation could also cache the var handle for a given field and likely apply other optimizations.

Testing

This completes the implementation work and we now can test the field reader spec API and the ACME implementation from within the user module:

public class MyEntity {

private String name;

public MyEntity(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

public String getName() {

return name;

}

}public class FieldReaderTest {

public static void main(String[] args) {

FieldValueReader fieldValueReader = FieldReaderApi.getFieldValueReader();

Object value = fieldValueReader.getFieldValue( new MyEntity( "bob" ), "name" );

assert "bob".equals( value );

}

}Note that the module descriptor of the user module doesn’t declare any dependence on the ACME implementation:

module com.example.beans {

requires fieldreader.spec;

opens com.example.beans to fieldreader.spec;

}Instead it is sufficient to add this module to the module path when executing the application, and the API module will bootstrap the implementation,

passing the PackageOpener object required later on to open the user’s packages also to the ACME implementation module.

As an experiment, try and omit the opens directive in the module descriptor.

This will prevent the API module from opening up the com.example.beans package towards the implementation module,

and you should see the following exception:

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.RuntimeException:

java.lang.IllegalCallerException: com.example.beans is not open to module fieldreader.spec

at acme.fieldreader.impl/acme.fieldreader.impl.FieldValueReaderImpl.getFieldValue(FieldValueReaderImpl.java:44)

at com.example.beans/com.example.main.FieldReaderTest.main(FieldReaderTest.java:12)

Caused by: java.lang.IllegalCallerException: com.example.beans is not open to module fieldreader.spec

at java.base/java.lang.Module.addOpens(Module.java:751)

at fieldreader.spec/fieldreader.spec.FieldReaderApi$PackageOpenerImpl.openPackageIfNeeded(FieldReaderApi.java:25)Summary

In this post we’ve shown how Java specifications can make use of the JPMS to bootstrap implementations and how implementation modules can obtain private access to classes from user modules.

This is often needed; for instance JPA providers must access the private state of entities if these mandate field access. Similarly, Bean Validation providers must access field values for validating field-level constraints. As we’ve seen, the user module must open up the packages with the affected types for this to work. For the sake of portability, the packages should not be opened up to specific implementations, though, but instead to the API module. The API module can then open packages from the user’s module also to spec implementation modules. This approach achieves the goal of portability between specs, while enabling spec implementations to perform the required private access operations.

Note that this requires Java specifications to define a module name to be used by all API modules created for this specification (fieldreader.spec in this example). Or, better yet, just provide a single API module which is shared by all the implementations. As an example, that already is the case for JPA as of version 2.2, where Hibernate ORM also depends on the javax.persistence:javax.persistence-api:2.2 artifact instead of providing its own artifact with the spec packages.

An alternative approach could be to have the user code itself bootstrap a lookup with private access and pass this into the API during bootstrap.

For several reasons that’s not ideal, though: the Lookup API is rather low-level and user code might fail to correctly implement retrieval of a lookup with private access.

Also, in container environments, the user code isn’t in control of bootstrapping APIs such as JPA or Bean Validation and thus cannot pass a lookup object.

Finally, if the user classes are spread out across multiple modules, it’d be a challenging task to collect the required lookups from all these user modules.

In comparison, the solution of opening up user packages to spec API modules and let those further open the user packages to implementation modules is much easier to work with.

Some adjustments to spec API modules will be needed for this. It will be interesting to see when the affected specifications will begin to explore the required changes and release updated revisions of their APIs as JPMS-aware modules. With the recent move of Java EE to the Eclipse Foundation and its rebranding as Jakarta EE, there’s a great opportunity for the community - i.e. you - to help with that!

You can find the complete source code for this blog post including all the three modules we’ve discussed in our examples repository.

In a follow-up post we’ll explore how spec implementations can deal with resources provided in application modules, for instance XML descriptors such as JPA’s persistence.xml file. If you got any feedback or suggestions for other related matters to discuss, let us know in the comments below. Looking forward to your ideas, thoughts, questions on the topic very much.

Many thanks to Alex Buckley, Alan Bateman, Guillaume Smet, Sanne Grinovero and Yoann Rodiere for their extensive feedback while writing this post!